Sean's Blog

Thoughts on history and culture.

Only You: The somewhat depressing history of Smokey the Bear.

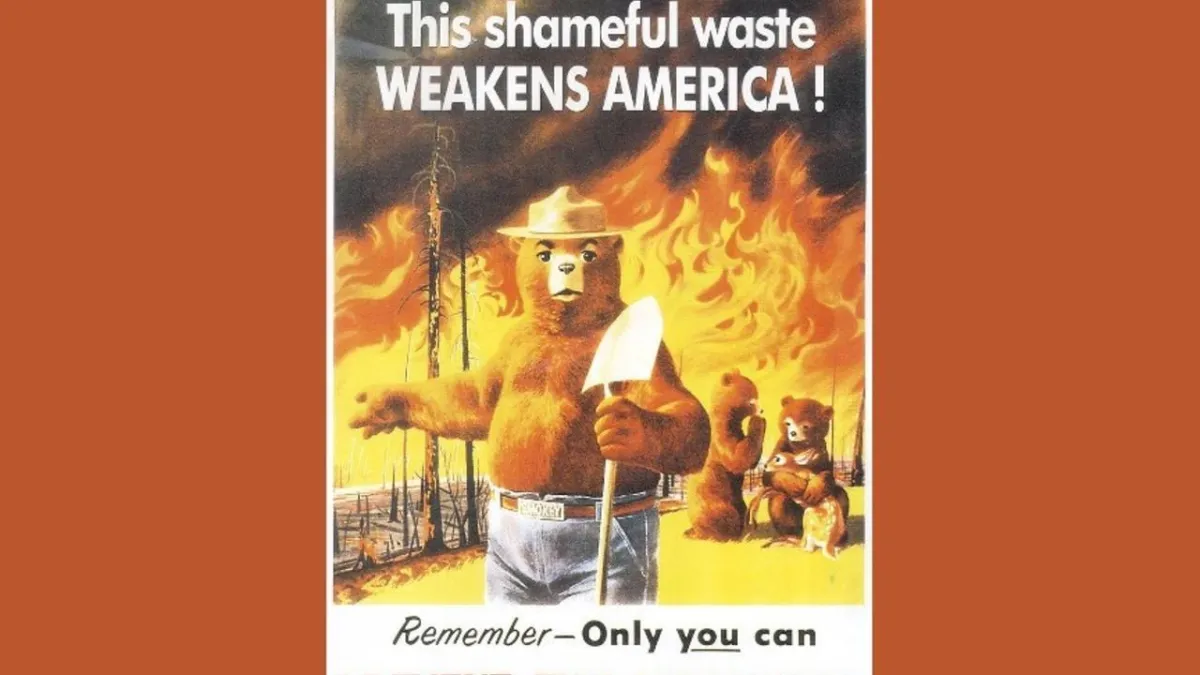

In the depths of World War II, on August 9, 1944, the U.S. Forest Service released a public service poster that featured for the first time a character who would become iconic in American history and popular culture: Smokey the Bear. The debut poster showed a black bear, in jeans and a ranger's hat, pouring a pail of water on a campfire above the caption, "Care will prevent 9 of 10 forest fires!" This wasn't exactly the most riveting message, but it was timely: with most young men off at war at the time, fire departments were very short-handed, and the Forest Service sought to shift its attention from fire suppression to fire prevention by getting the public to help. After the war the character of Smokey appeared on its most famous poster, which itself was a derivative of the old military recruiting posters of World War I. The 1947 ad first featured the immortal slogan: "Only You Can Prevent Forest Fires." Since then, almost every child raised in America has known who Smokey the Bear is and why he exists, marking one of the most successful PSA campaigns in the nation's history.

Smokey worked because he seemed so wholesome and innocent. The character obviously channeled Theodore Roosevelt and the teddy bear--one of America's most iconic folk images--and the fire prevention message resonated in part because Roosevelt was closely associated with conservation and environmentalism in the early 20th century. Smokey also lent a participatory message to civic responsibility and democracy: everybody, even children too young to vote, can share the responsibility to preserve America's forestland. Plus, anthropomorphic bears are hard to resist as lovable characters, and lend themselves well to being made into toys, postage stamps and costumes for park rangers to put on. There is, however, a dark side to the Smokey the Bear legend, and it's one that rarely gets talked about.

Smokey the Bear was a powerful icon in print media, and later on television. This public service announcement from 1970 shows the typical approach.

The Forest Service's Smokey campaign was very successful, but environmentally speaking, it may not have been the best idea. Beginning in the early 20th century, the federal government--principally the Forest Service, but also other agencies like eventually the BLM and the Bureau of Indian Affairs--committed themselves to an operational model that mandated full suppression of fires in national forestlands, wherever they occurred. Sounds like a good idea, right? Well, ecologically, it's not that simple. Many forest fires are started by humans, whether negligently, carelessly or deliberately, but some are also natural, such as from lightning strikes, and they are part of the ecological process of clearing out small brush and downed branches from the forest floor. Not all forest fires are bad. The government's tendency to treat them that way, however, especially in the 1940s when Smokey debuted, meant that this brush built up in many forests. When they burned, the intensity of the fires was often much greater than it would have been under natural conditions. This paradigm did not really begin to change until the 1970s, when the relatively new science of ecology began to take hold at policy levels, recognizing that the balances of forest ecosystems are more complex than they seemed.

Unfortunately, we are still living with the results of the "pure suppression" model. In the past few decades, wildfires have grown progressively more catastrophic, in large part due to drought and climate change, but also because too few forests have been "managed" to reduce the underbrush fuels that can make fires much worse than they should be. Furthermore, as more people move to fire-prone areas, especially in the West, they bring with them an assumption that it is the federal government's responsibility--not theirs and not their local communities'--to protect them from wildfires. Ironically the "Only You" and Smokey campaigns obliquely reinforced this assumption. It's your job, said Smokey, to prevent fires, but suppressing them once they start is someone else's. The federal government can't shoulder the financial burden alone, especially in the era of climate change.

Over the years various real bears have "played" Smokey, usually at the National Zoo in Washington. Here is the animal that was playing the role in 1984.

Beyond policy and environmental science, the lovable nature of Smokey proved perhaps not so lovable for a couple of real world bears who found themselves unwittingly portraying the character. In 1950 a black bear cub was rescued from a forest fire in New Mexico. After being cared for by a local game warden, the cub, who invariably became the "real" Smokey the Bear, caught the attention of the media. As children clamored to see the injured cub, a decision was made to house him at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., where the animal was essentially incarcerated until its death in 1976. Other bears ended up "playing" Smokey under similar circumstances. As recent controversies regarding Sea World and its orcas have highlighted, societal attitudes are beginning to change regarding the ethics of keeping wild animals in zoo-like enclosures. Zoos have always been a bit uneasy for me. I've always liked seeing fascinating animals--who doesn't?--but I've always felt vaguely sorry for them at the same time. Bears are especially pathetic in captivity, and one can easily imagine the misery of bears singled out for special attention by "being" Smokey.

There have been some tweaks to the Smokey phenomenon, which interestingly seem to validate some of the criticisms of the character and the campaigns associated with him. The last "real" Smokey the Bear died in captivity in 1990 and has not been replaced. In 2005 the Forest Service changed their slogan from "Only you can prevent forest fires" to "Only you can prevent wildfires," raising a distinction between desirable and undesirable fires. And the character in general is less ubiquitous in PSAs and popular culture than it was 50 or even 30 years ago. In a broader scope, federal wildfire policy is changing. It has to, because present models are financially unsustainable.

Smokey has proved to be a cultural icon as well as a political statement. Here are two tourists posing in front of a Smokey statue in Minnesota, circa 1973.

As fun a character has he has been for over 75 years, I'm not sure Smokey the Bear has really done a lot for us in the real world. The whole phenomenon strikes me as sort of a reductive, blunt-instrument approach to the issue of forest fires, where a bit of nuance and forethought might have served us better in the long run. I'm not going to go so far as to denounce Smokey, who is, after all, as American as apple pie; but let us acknowledge at least that his legacy is not as squeaky-clean as the character we wish he was.